[I’m re-upping this post as I’ve seen a number of new subscribers who might have missed it and because it’s indicative of something new that I’m working on. I’ve also fixed a couple of broken links! Enjoy"!]

This is the first of two articles about the weird world of defence marketing. In this article I’ll focus on my thesis - about how defence marketing has always been about the widest possible audience. In the article to follow I’ll focus on how two defence tech champions have applied these lessons in their marketing materials.

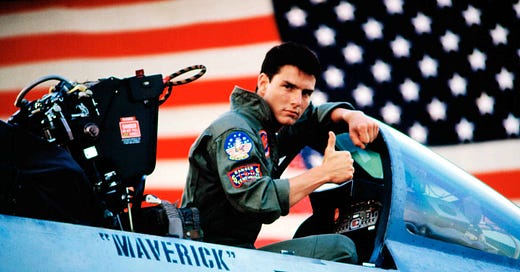

When I was 10 years old, Top Gun arrived in the cinemas (when I was 10 we still went to cinemas). For kids around the world of my age, Top Gun was an intoxicating mix of male bravado, 1980s American martial optimism, late Cold War posturing, and marketing (yes really), lots of marketing. All those F-14 Tomcats and aircraft carriers were very, very expensive product placements.

The brains behind this glossy piece of content marketing was Jerry Bruckheimer, a former adman turned Hollywood producer. Through the 1980s and into the 90s, Bruckheimer perfected this genre of filmmaking with an addictive mixture of drama, excitement, stupendous budgets and a high frequency of explosions. In my opinion, Top Gun was the apex of this genre. Bruckheimer’s ‘client’ - the US Government and in particular the US Navy - donated the hardware, the sets, and the extras - and Bruckheimer supplied the star power and the drama.

The film was a global hit, and its star, the fresh faced Tom Cruise was on his way to becoming an icon. But a side effect for a generation of impressionable youngsters (howdy), had other impacts: the armed forces became aspirational, even sexy; we were absolutely the good guys; and all that hardware, combined with smart, capable people, and yes, a few mavericks, would overcome the bad guys. Of course a 10 year old doesn’t process things with that kind of analysis, they just feel it.

But Jerry Bruckheimer was an adman - he knew that the feeling is what matters most.

The Wilderness Years

Not unexpectedly the end of the Cold War brought an end to this period of defence content marketing. Jerry Bruckheimer’s own credits can give a picture of this change of mood - Crimson Tide (1995); Enemy of the State (1998); Blackhawk Down (2001) - chart a course of introspection and distrust compared with the confident certainty of Top Gun. This was only heightened by the reaction to the Iraq War in 2003. The point of this article is not to detail the political or psychological impact of this period on the Western psyche, but there was a notable impact on marketing for defence companies.

The armed forces themselves continued to market service in the armed forces in similar forms to Top Gun (why mess with a formula like that). But defence companies and primes - think Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, BAE Systems and others - didn’t quite pick up the gauntlet.

Oh sure you can’t walk through Westminster Tube in London or around Washington DC without seeing large ad placements for BAE Systems or Lockheed Martin, but those ads are very targeted towards policymakers and defence procurement people. These ads give a very clear message of “Look, here’s a picture of a missile/aircraft carrier/helicopter/fighter jet you paid us to billions build! Please think of us when you want to build your next missile/aircraft carrier/helicopter/fighter jet! Did we mention that we are also a very nice place to work?”

The marketing of these products is sterile and cold. The language became euphemistic or very safe, the audience a very narrow set of decisionmakers, the messages seemed to avoid the nature of what defence brands do.

And then 2022 happened

I’m marketing guy, not a historian, but I do have a suspicion that in the future when historians look back at this period, 2022 will be a very important year. For the purposes of this article, 3 important things happened in 2022 that form part of my thesis:

Russia invaded Ukraine. Although Russia had been steadily consuming its neighbours for decades, the invasion of Ukraine in February was a moment when the scales fell from the eyes of many in the Western world. ‘History’ was back. This was not “little green men” or the consuming of an unfortunate small state in central Asia. This was gigantic military invasion by a hostile country on the doorstep of Europe, a few hundred kilometres from NATO’s borders. The shock of this action was so large that even the ESG industry belatedly realised that their well-meaning but poorly thought through objections to defence investment might be doing more harm than good. Alongside this realisation, the pretentions of the tech industry and its objections to working on defence projects were evidenced as being harmful to Western interests. Palmer Luckey and Anduril were proven right (more on this later).

Elon Musk acquired Twitter. Though not specifically crucial to this story, it is notable because it set in motion a preference cascade in which more and more people felt comfortable to express the idea that perhaps defence spending is a good thing without being shunned as warmongers.

Top Gun: Maverick was released. 28 years after the original film, Tom Cruise reprised his role as Pete “Maverick” Mitchell. Training a new generation of pilots, fighting new enemies, winning the new vibe, and yes wearing the correct Taiwanese flag on his leather jacket. The film was fun, critically acclaimed, loved by audiences and was a box office hero.

So 2022 was important. It reminded everyone that defence spending was absolutely, something we all need to talk about, and when done the right way, actually quite cool.

Marketing is about emotions

Hopefully you’re still with me at this point and wondering what all this has to do with marketing for defence! I’m getting to that.

There are many theories about marketing, but the one that I subscribe to is that all marketing must work at an emotional level. The reason is that whether we like it or not, we all make decisions at an emotional level whether we realise this or not. Even making a purely rational decision can have an emotional basis if you’re the sort of person who places a high value on rationality.

With that in mind, I’d like you to watch this clip which, I kid you not, is also from 2022:

Elon Musk at US Airforce Academy in 2022

The clip is from a visit that Elon Musk made to the US Airforce academy. Look at the reactions of the graduates. Can we imagine any other politician, business person, sports star, celebrity or literally anyone receiving such a wildly positive welcome? The graduates respond to him at a deeply emotional level. Why does Elon elicit such positive emotion? Elon is stupendously wealthy, but people don’t respond to wealth like this. Tesla is an exciting and innovative company, but not enough for this kind of response.

The key here is SpaceX and what SpaceX has done for the US efforts in space and defence. Since its founding 20 years before this clip, SpaceX has gone from being a pipedream and a joke in the space industry to the absolute backbone of NASA, US military space program and much else. With SpaceX, Elon Musk dared and won over and over and over.

My contention is that these graduates respond to Elon with such emotion because he is their Champion - not a champion, but their champion in the Medieval sense of the word. Their support of Elon here is visceral and deeply emotional because he builds the tools that enable the US victory, prestige and power on the world stage. Through SpaceX, Elon ‘fights’ for the USA and wins. Because of this, the people who physically fight those wars love Elon with a passion approaching hero-worship.

And with that thought in mind, do you notice anything familiar from this clip?

At its basis, all marketing for defence companies should be looking to tap into this kind of emotion, because it is the basis of the entire defence industry: Keep us safe, make us great. It’s difficult to think of any other motivators this powerful. The major defence companies do not do this. But other defence companies can and do. So let’s look at how they’re doing it.

The ‘Consumerisation’ of Defence

In marketing shorthand, a ‘consumer’ is an end user or the person buying the product or service for personal use. So a B2C company is a business that sells to consumers and while it might distribute through other business, it typically markets directly to those consumers. Apple is a consumer brand, McDonalds is a consumer brand, Balenciaga is consumer brand, Proctor and Gamble owns a portfolio of consumer brands. The brand of a B2C company should “live” in the mind of its consumer audience and demand from consumers should “pull” sales through distribution channels. There’s a plethora of variations, but in essence a consumer brand works in this way.

Of course, consumers can’t buy military hardware, but given the role of defence in our societies, the procurers (government), the users (military services) and the beneficiaries (us) are all “consumers”. So what do I mean by “Consumerisation of Defence”? Returning back to Top Gun, Jerry Bruckheimer and the US Navy, through the medium of an action film, allowed everyone to feel connected to purpose and method tools of defence, they “Consumerised” it.

Top Gun is impossible without mavericks

Earlier I mentioned Palmer Luckey, cofounder of Anduril. If you have the time, I strongly recommend you read the profile I linked to from Tablet. Its a fascinating read.

If there’s another maverick entrepreneur who is on track to reach Elon Musk levels of fame, it’s Luckey. Like Elon, Palmer took enormous risks - financial and reputational - when founding Anduril Industries in 2017. This was a period in tech when the post-Trump backlash was in full effect and tech companies were pulling out of defence projects to quell internal unrest. Founding a defence company was hugely contrarian. The business model was also contrarian - where defence primes like Raytheon or Lockheed Martin will build new weapons and platforms on a cost plus basis, Anduril would research and build new defence products and sell them “off the shelf”.

By choosing to work this way, Anduril assumed all the product and financing risks, but was able to sell to its customer - the US govt and US allies - at a fraction of the costs of the primes, while also being more nimble and innovative. But choosing this business model also has a significant impact on marketing - instead of selling to people who write RFPs, you’re now marketing to a handful of key audiences:

Government procurement people. Naturally someone has to pay for this stuff. If you can help them feel good they’re buying the best kit and saving Uncle Sam a lot of money, the so much the better!

The service-people who use the tools. If you’re fighting the enemy, you have a really keen interest in knowing you have the best tools for the job. Fortunately for Anduril their close links to fighters in the field both helps them with product development AND brand development.

Potential employees. When it was founded, Anduril had the pick of the talent who actually believed that defending yourself was a morally good thing to do. Since 2022, many more people have woken up, as has the competition for talent. Marketing is crucial in the war for talent.

Everyone at home who is kept safe. The people who ultimately pay for the defence - the taxpayers, want to know their military has the best kit and ideally at the best price.

Your adversaries. More than anything else, defence is about deterrence. Preventing conflict is the first and primary purpose of defence. If your adversaries know and fear your brand, you can help keep the peace.

Which returns us to the point I made at the start of this post - you’re now talking to a much bigger audience, a consumer audience. Because of this, your marketing toolkit must look and operate more like that of a consumer brand. And that is the focus of my next article.

To be continued…

In the next post I’ll focus on the toolkits used by two defencetech brands - Anduril and Helsing - to appeal to a much broader audience in their metaphorical battle for hearts and minds. So subscribe to get this post, and many more, direct into your inbox.